Suit Up! Historically speaking...

- Nicole (Nico)

- Oct 28

- 8 min read

A fellow dance student recently asked me if it would be OK to dress up as a belly dancer for a Halloween party.

I couldn’t give her a straight ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ so I launched into my usual evasive verbal maneuvers - namely, asking her what exactly she meant by ‘dressing up as a belly dancer’. Because nothing quite declares “I am a hopelessly committed nerd” like delivering an hour-long lecture on the evolution of belly dance costuming!

Unless you’ve been immersed in the world of raqs sharqi and its many controversies for years - chief among them the dramatic, ‘The costumes became too revealing, too sexy, too scandalous!’ - then when you picture a belly dance costume, you’re probably imagining a heavily decorated hip sash and a bra-like top with matching embellishments, and a flowy skirt.

It’s a very recognizable image - so much so that we collectively treat this belly dance getup as a sort of professional uniform. We’ve even gone so far as to appropriate an Arabic term for it, just to streamline communication and, of course, make ourselves sound a little more ‘in the know.’

The word bedlah (sometimes anglicized as badlah) simply means ‘suit’ in Arabic and can refer to any such outfit - including a man’s tailored suit.

There’s something deliciously ironic about a word that can describe a funeral attire being equally applicable to a shiny bundle of sequins, fringe, and strategic double-sided tape!

Unless you dance strictly theatrical folklore, chances are you either own a bedlah (or twelve) - or have at least worn one on stage. The bedlah has been a staple of raqs sharqi costuming for ages… or has it?

Let’s tumble down a historical rabbit hole, Dorothy, and take a gander at what existed before the bedlah stole all the glittery attention.

I’m setting our free-fall destination in the first half of the 19th century. Partly because I want to show you a quote that sets the stage for what’s to come - and partly because, frankly, my knowledge of Egyptian belly dance history doesn’t stretch much further back than that. The French occupation of Egypt in the late 18th century did leave behind some historical records relevant to today’s topic, but I’ll leave the joy of digging through those early Orientalist accounts to you - as homework. You’re welcome.

“68 Dancers The almées are generally young and pretty women; they are both artists and courtesans. Their costume is almost the same as that worn by the elegant ladies of the country and which we have already described, but it is imbued with this particular character which everywhere distinguishes the exterior of the gallant woman from that of the honest lady. Thus their clothes tighten and outline the forms more; their throat is uncovered; their arms are bare; there is in their adornment the search for the most precious fabrics, affectation of wealth, profusion of gold and jewels.” (Clot-Bey, A.B. 1840. Aperçu Général sur L’Égypte. Tome Deuxième. Paris: Fortin, Masson et Cie.***Translated by Google)

It’s quite clear that, at the time of Clot-Bey’s writing, professional dancers did not wear a badlah or anything resembling it. Their “costuming” consisted of the everyday attire of middle- and upper-class Egyptian women. Of course, some modifications to dancers’ “costume” were inevitable - necessary, even - to enhance the performance and highlight the carnal nature of their art.

The key difference was that “honest ladies” would always wear a modesty garment - such as a thobe and a bur’a - over their regular clothing when appearing in public spaces.

So, what did women not involved in professional entertainment wear in Egypt at that time? Fashion among the general populace closely followed the trends set by the Turkish-Ottoman elite and was largely indistinguishable from styles seen throughout the vast Ottoman Empire.

Let’s make a list of clothing items typical of middle- and upper-class Egyptian women.

For more detailed descriptions - including fabric types, colors, and how these varied by socioeconomic status - I highly recommend reading Edward William Lane’s chapter “Personal Characteristics, and Dress, of the Muslim Egyptians” in its entirety. We're focusing primarily on the section describing women’s clothing, which begins on page 41. It’s far too long (and detailed) to quote here in full, but well worth the read.

Chemise or undershirt: typically made of gauzy, lightweight, and often sheer fabric. By the mid-19th century, it had shortened to about knee length; however, earlier records indicate that undershirts were considerably longer in previous decades.

Yelek: made of a more structured fabric, this garment is fitted to the waist with side slits below the waistline. Although it buttons down the front, it still reveals much of the chemise-covered bosom underneath. Typically floor-length, it could even extend a few inches beyond that.

‘Antaree: essentially the upper half of the yelek - a fitted, long-sleeved, jacket-like garment that extends only to the waist.

Shintiyan: better known to modern-day dancers as pantaloons — very wide-legged, billowy trousers. The bottoms were tied just below the knee yet were long enough to drape to the floor or at least reach the feet.

Shawl: most commonly a square piece of cashmere, or other fine wool fabric, folded diagonally in half and wrapped loosely around the waist.

Sudayri: a short vest worn between the undershirt and the yelek (or antaree) during cooler weather, such as in the winter months. Keep this garment in mind - it will become a prominent feature of belly dance costuming in the latter half of the 19th century and beyond.

Not included in this list for the sake of brevity - but still worth mentioning - are shoes, headwear, jewelry (including amulet boxes), hair adornments and hairstyles, modesty garments, and, of course, tattoos.

So, if you’re struggling to piece it all together and imagine a professional entertainer from this era, here’s a handy visual aid: Egyptian Dancing Girls by Luigi Mayer (aquatint, 1802)

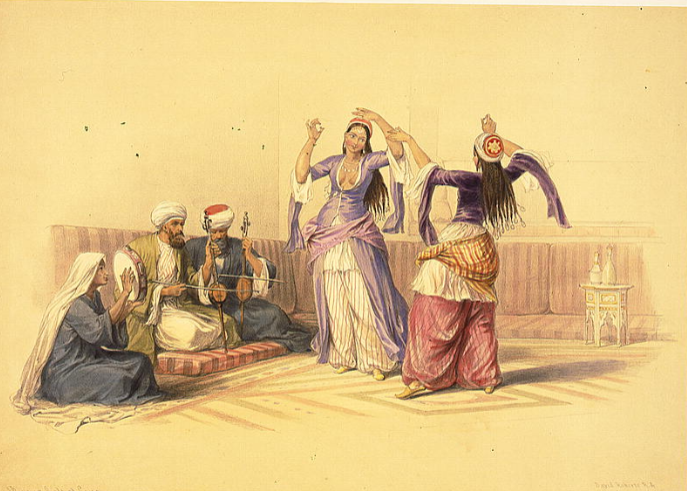

In this drawing by David Roberts, Dancing Girls at Cairo (1840s), the dancer on the left sports a yelek, while the one on the right rocks an antaree.

If you'd like to compare a "gallant woman" to an "honest" one, here is an illustration from E.W. Lane's book I linked above. Note the title: “A Lady in the Dress Worn in Private.”

The fashion of the Ottoman elite evolved as the 19th century progressed and so did the dancers’ professional attire. The antaree became more popular than the long yelek, and sudayri were no longer limited to winter wear but in some cases fully replaced the antaree. However, yeleks still maintained their presence in more rural settings - unsurprising, considering that the pace of fashion inevitably slows the farther one gets from the capital.

Drawn images are great, of course, but the advent of photography truly expanded our collective understanding of professional dance costuming in the mid-19th century.

Here you can see a photograph by Ernest Benecke titled Zofia, Femme du Caire. The second photo features the same woman and is titled Zofia, Intérieur du Harem. Both shots were taken in 1853.

If you browse through this fascinating and eclectic collection of early photographs, you’ll also find an image from a year earlier - 1852 - by the same photographer. Note that the lady smoking a hookah is wearing sheer chemise, with her sudayri and shintiyan made of matching fabric.

“But wait, Auntie,” you might say, “what makes you think those women were dancers? There’s nothing to indicate they were professional performers!” You’re absolutely right. It seems like most dancers were photographed wearing their finger cymbals, since zills were a non-negotiable part of any dance performance in earlier years.

Side note: it might just be my luck, but the majority of late-19th- to early-20th-century photos of dancers with cymbals that I stumble across on the interwebs show them holding the finger cymbals in the closed position. Makes one wonder why…Every time the Cymbal Ladies of my dance tribe strike a pose for a photo, we make sure to hold ours open - because nothing says “I suffer for my art” quite like flashing your shiny little torture devices for the camera.

Back to the question of profession. Those women could be dancers - or they could be prostitutes. Or, quite possibly, both. In the public eye of the time, the two were often indistinguishable anyway. One thing is certain, though: these women were not of high social standing. No woman of “respectable” status would have allowed herself to be photographed without her modesty garments - head covering, veil, and all.

Fast forward to the late 19th century. The following images by Gabriel Lekegian are instantly recognisable to anyone interested in the history of raqs sharqi.

A great deal had changed in the preceding decades, especially in fashion. Ottoman dress had absorbed more European influences, which translated neatly into dance costuming. The undershirt, once knee-length, was now cropped at the waist; the yelek and ‘antaree were replaced entirely by the sudayri; skirts, adorned with imported lace trims, made their debut - though some dancers still preferred to wear shintiyan under a skirt rather than stockings. European-style heeled shoes became popular.

Most notably, the diagonally folded shawl gave way to a ribbon belt.

This marks the first recorded instance of “a special outfit just for performing” - the birth of the Egyptian dance costume. The ribbon belt had no equivalent in the everyday dress of the middle- or upper-class women of late 19th-century Egypt.

The Raqs Sharqi Museum has an outstanding collection of drawings, lithographs, etchings, and photographs from the period we’re exploring. I highly encourage you to browse through them, note the year of each piece, and trace the changes you spot from one era to the next. It’s a fascinating - if delightfully nerdy - game to play!

So here we are, at the turn of the 20th century. Do indigenous entertainers have a professional uniform? Well, sort of. Their outfits are recognized as costumes, but not to the extent that we “costume” ourselves for performances today.

In keeping with pretty much everything else, Egyptians didn’t simply absorb all Western influences wholesale - they selectively adopted and adapted what worked for them.

Surely you’ve heard the claim that the bra-belt-skirt combo - the bedlah - was introduced by Hollywood and Western art in general. The story goes that Egyptian dancers saw how Europeans portrayed the “Orient” and adapted their costumes to please their Occidental patrons. This, however, is highly unlikely.

First, the timing is off - what we would recognize as a bedlah didn’t really emerge until the 1930s. Second, the natural evolution of belly dance attire into the bedlah was, frankly, inevitable. Look at the images above and tell me you don’t see the connection! The bust and hips are accentuated, the mid-torso exposed yet visually softened by the more striking fabrics above and below it. Those tiny, glove-tight vests kept shrinking and the sheer undershirts were eventually abandoned - only to be partly replaced later by shabaka (belly cover) to appease the censors.

It doesn’t look like Egyptian dancers were rushing to adopt those absurd “disk bras” that Western fantasy insisted were the sensual attire of mysterious Oriental dancers!

Let’s not strip the traditional professional entertainers of MENAHT of their agency - or, worse, assume that whatever they did was simply to please their colonizers.

Every innovation in belly dance costuming that we have a historical record of seems to be a natural response to organic changes within its source culture. This was as true a century ago as it is today.

And speaking of the last century - there’s much to be said about the evolution of costuming in the early 20th century, before the glitz and glamour of the Golden Era of Egyptian cinema took center stage. I might just do a part two to explore some of the fascinating developments from that period…No promises, though, Dorothy - I value my (in)sanity far too much to commit just yet!

Think I’ve committed a historical atrocity? Consider this your official invitation to nitpick!

_edited.jpg)

Comments