- Auntie Helen

- Dec 30, 2025

- 10 min read

What would you rather do: read yet another long ramble about a hyper-specific, deeply niche topic that will warm only the cold, shriveled heart of a hopeless nerd - or stub your toe on a chair leg?

The choice is obvious! Chair, brace yourself.

As much as I thrive on researching every obscure corner the history of belly dance has to offer, switching from laid-back holiday mode to the Type A academic persona you know (and tolerate) is a tall order for me - even with the help of elevated caffeine concentrations in the bloodstream.

So, in the interest of gently easing all of us into a new year of research and learning, I’ve decided to start with a slightly different format. Chill, Dorothy - we’re not going down any rabbit holes today.

Okay, that’s probably bullshit, but I do promise the rabbit holes will not be too deep.

My primary agenda today is to introduce you to a few belly dance-specific terms that you’ve most likely heard in class or at a workshop - terms you sort of, kind of understood from context, but never actually bothered to look up to see whether your gut feeling about their meaning was correct.

What follows will be most helpful if you’re new to learning all things belly dance, especially if your focus so far has been on the kinesiology of this art form.

The terms will appear in no particular order, other than the number of times I’ve watched people’s eyes glaze over when I carelessly drop them into conversation. A couple are included purely to spare you from having to reread my earlier blog posts - this time presented in a more focused and concise manner, rather than as a long diatribe from an opinionated wanna-be scholar.

A final note: we all have our preferred ways of transliterating non-English words. Serious academics and researchers aim for phonetic precision. I, being neither, aim for whatever makes sense to me personally - meaning I can actually remember how to spell it without having to Google it every single time. I’m also wildly inconsistent and feel no obligation to commit to one way of spelling. Consider it a sprinkling of spice on an otherwise bland reading menu.

Down we go!

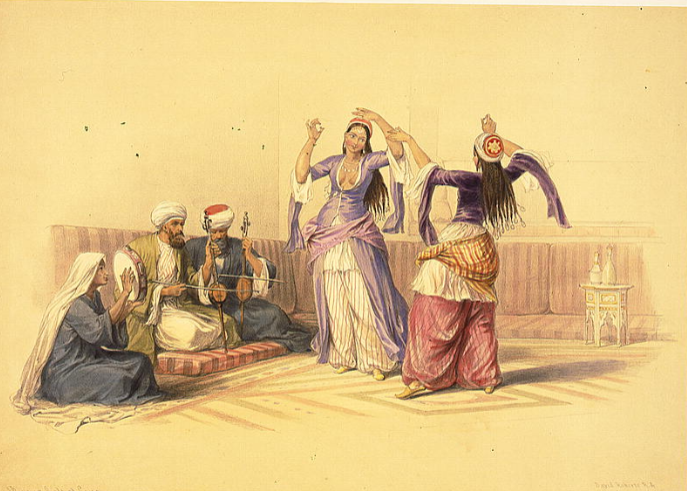

First on the list is awalem. This is the plural of almah - commonly rendered as almeh in early Orientalist literature. The literal translation is deceptively simple: “a learned woman.”

And this is precisely where all simplicity is going to die, because awalem is a term loaded with complexity and nuance, its meaning shifting significantly over the past couple of centuries.

“Learned woman,” in this context, does not refer to academic or scholarly training, nor does it imply expertise in the sciences. Rather, the term almah was used to describe a professional female entertainer with a broad and versatile repertoire. An almah was expected to sing, dance, play musical instruments, recite poetry, and otherwise entertain an audience. In short, she was a well-rounded performing artist.

Interestingly, according to belly dance researcher Heather D. Ward, there is currently no evidence of the term being used prior to the 18th century. This does not mean that the profession itself did not exist before then - only that the word awalem was not yet used to describe women engaged in such work.

Awalem were particularly popular among the upper classes, where they most often performed in the privacy of the women’s quarters. This allowed the women of the household to shed their modesty garments and enjoy the full performance, while the men were relegated to listening from behind a moucharabiya screen. There’s this whole other aspect about how women of the upper crust could watch the chaos of daily life, street performers, and random public spectacles from behind the same screen, without being dirtied by the gaze of the unwashed masses - but we won’t go there today!

There is ongoing debate about whether awalem were dancers as well as singers, or singers only. I will spare you the lengthy citations arguing both sides and instead remind you of one simple truth: nothing - and I emphasize nothing - in Egyptian history is ever cut and dry.

In short, practices varied. But for the sake of a more accurate and inclusive reflection of reality, we’ll assume that awalem were both singers and dancers.

It is important to keep in mind that, although awalem performed for the elite, they themselves did not belong to the elite class. On the contrary, they most often came from lower social strata and were perceived accordingly, despite being an indispensable part of celebrations marking all stages of life.

Events such as a sebou (a child’s seventh day of life), circumcisions, saints’ birthdays, and other major milestones could not be celebrated without the presence of professional entertainers.

The culture - or the institution, if you will - of the awalem tradition appears to have died out by the end of the 20th century, and there are no known practicing awalem in Egypt today. This decline was the result of multiple factors, the most significant of which was the 1952 revolution.

Yes, my favorite dead horse is back again!. Allow me to beat it - enthusiastically - once more: traditional entertainers did not align with the government-imposed vision of Egyptian national identity. As a result, a profession that had existed for centuries was gradually pushed into decline and ultimately erased.

The definitions have shifted yet again. Today, traditional female entertainers of the past are often held up in contrast to modern professional performers - usually by someone arguing that “belly dance has turned into gymnastics (or striptease, or whatever floats their angry little boat), that it’s too sexual, too revealing, too vulgar, blah blah blah… unlike the modest, proper awalem of the good old days.”

Well, Dorothy, I trust you know better by now.

In conclusion, awalem can be defined as skilled professional female entertainers who primarily worked in private, high-class, gender-segregated settings.

This segues beautifully into the next item on the list: ghawazi. Surely you’ve heard the term before - most likely delivered with a tremble in the voice, along the lines of: “Khayriya Mazin is the very last practicing ghawazi left on this planet. When she dies, the art of ghawazi will perish forever.” Cue ominous violin music.

To understand why this claim is… let’s say deeply weird, we first need to clarify what ghawazi is not.

It is not a tribe. It is not an ethnicity. It is not a religious sect.

Ghawazi is the plural of ghaziya (female) or ghazi (male). Since we’re focusing on women here, I’ll stick with ghaziya for the singular.

Despite what 19th-century Orientalist writers - and, regrettably, some much more recent authors - would have you believe, ghawazi describes a multi-ethnic profession, not a monolithic cultural group.

Now, a necessary warning label. In Western dance circles, ghawazi is usually treated as a neutral - or even romanticized - term. In Egypt, not so much. There, it functions more or less as an insult, and for very specific reasons: historically, ghawazi occupied the lowest social strata of Egyptian society. They were poor, marginalised, and socially stigmatised - yet somehow indispensable. Just like the awalem.

So, what are ghawazi? I will shamelessly repeat myself and say they are professional female entertainers with a broad and versatile repertoire.

“But how are they different from the awalem?” you might ask, dear Dorothy. Oh, I’m glad you did, because the differences are real - and not remotely trivial.

While awalem primarily performed in private, elite, gender-segregated settings, ghawazi worked very much in the public eye. They sang, danced, and played drums in the streets, performing for mixed, unsegregated crowds of all genders and low social classes. Because ghawazi mostly performed in public spaces, they were visible to anyone who happened to be present. It is therefore inaccurate to claim that they never entertained members of the upper classes. Social status does not confer invisibility, and elites, much like everyone else, occasionally found themselves on the same streets, squares, and festival grounds as everyone they publicly pretended not to notice.

Another key difference lies in how women ended up in these professions in the first place. Most awalem appear to have entered professional entertainment from outside established performer families - very likely due to good old-fashioned financial insecurity. While it is not entirely impossible that a young Egyptian girl awoke one morning and thought, “You know what sounds fun? To be a professional entertainer when I grow up, because nothing screams life goals like being widely assumed to be a normative-gender-role-bending harlot and general moral menace,” such a scenario seems… unlikely. Possible? Sure. Probable? Let’s not insult statistics.

By contrast, ghawazi were far more commonly embedded within familial and hereditary performing networks. Profession, reputation, and social status were transmitted intergenerationally, making entry less a matter of individual choice than of birth and kinship. It turns out that escaping a “disreputable reputation” is much harder than simply marrying someone who already shares it.

In short, while awalem often entered the profession through circumstance, ghawazi inherited it wholesale - along with the music, the movement, and a social standing so low it practically came with a basement suite.

As time went on and the distinctions outlined above became less pronounced, a new internal division emerged within the broader category of traditional female entertainers. Awalem increasingly came to be associated with performances in urban centres, while ghawazi were more commonly linked to rural settings. Despite this geographic differentiation, both groups continued to fulfil the same essential social functions they had for centuries: serving as indispensable participants in life-cycle and communal celebrations, including weddings, mawalid, circumcisions, and other festive occasions.

The labels became imprecise, the settings evolved, but the work itself - necessary, marginal, and structurally unchanged - remained remarkably consistent.

An important note on geographical distinctions within ghawazi performance traditions: there are clear stylistic differences between Upper Egyptian ghawazi and their Delta counterparts. These differences extend well beyond musicality and costuming, but a detailed discussion of them falls outside the scope of this post.

It is worth keeping in mind that Khayriya Mazin represents an Upper Egyptian ghawazi style, filtered through her own personal and familial Mazin lineage. So please - before you run with it - do the research and consult multiple sources. And if you choose to style your performance after any ghawazi artist, proceed with both caution and respect.

Moving on.

Zeffa (singular) and zeffat (plural) refer to a parade or ceremonial procession. Zeffa al Aroussa is the bridal procession. During a wedding celebration, the bride and groom are escorted from the bride’s parental home - where she grew up - to her new home, the one she will now share with her husband.

In modern contexts, this may look like a procession down a hotel hallway into the reception area, or perhaps a grand loop around a room packed with guests. Traditionally, however, the procession took place in the streets and included musicians and other professional entertainers. It was not uncommon for a zeffa to feature more than one dancer; increasingly elaborate zeffat became a point of neighborhood bragging rights and a competitive exercise in ceremonial dick-measuring among neighbors.

Although the Zeffa al Aroussa is ostensibly all about the bride, it is the dancer - or dancers - who lead the way, sometimes with a lit candelabrum balanced on their heads.

Yes, Dorothy, this is how raqs el shamadan entered the narrative. Cue yet another “it’s a myth but honestly, who even cares anymore?” eyeroll.

Quick note: there is a Zeffa 4/4 rhythm. It goes something like Doum-tek-ka-tek-tek, Doum-tek-tek and has a beautiful, ceremonial feel.

And while we’re at it, let’s talk about the next word on the list - shamadan. A shamadan is a candelabrum - or a candelabra. Since I genuinely do not know which term more properly applies to the large candle holder in question, feel free to pick your preferred linguistic hill to die on. English isn’t my first language, after all - yes, I’m absolutely playing my get out of jail free card here.

Shamadans for dancing can be either free-standing or mounted on a specially made, helmet-like base that is supposed to help balance the metal motherfucker on your head. Allow me to burst that bubble using lived experience: unless you add ties that go behind the head (artfully - or not - concealed under your hair) or a chin strap, the helmet does very little to help. What it does provide is a false sense of security. Credit where credit is due!

In practice, a well-balanced free-standing shamadan is almost always easier to dance with than an unbalanced candleholder attached to a migraine-inducing head cage masquerading as “support.” One relies on physics and skill; the other relies on vibes and misplaced optimism. That said… if I had to choose between balancing a crappy helmet-based shamadan or never experiencing the thrill of dancing with a shamadan at all, I’d always pick the former. But, as always, you do you!

And now, after I’ve pontificated at length on some of the notoriously misunderstood terminology of Egyptian belly dance, let’s wrap things up with a gentle reminder of the alternative name we often use for this delightful art form: raqs sharqi.

“Raqs” simply means dance, while “sharqi” translates as eastern or of the east. Crucially, this refers to the Eastern Arab world, not the fuzzy Orientalist notion of “everything east of Europe.” And while we’re at it, let’s throw raqs baladi into the mix for good measure. “Baladi” literally means of the country or of the homeland. In practice, it most commonly refers to the social form of dance related to raqs sharqi - danced by people of all ages and all genders at celebrations, gatherings, and life events.

Hopefully, this quick run-down ahead of the new season of dance classes will help you approach it with a bit more enthusiasm - and, more importantly, with a greater appreciation for nuance.

I’ll leave you with two final thoughts.

First: several of the topics that came up today have been explored in far more detail elsewhere in my writing. One dives into the history and origins of the term “belly dance” itself; another unpacks raqs el shamadan; and yet another gleefully dismantles the endlessly recycled myth of who supposedly gets credit for being the very first shamadan dancer. Those who seek, shall find. It’s all out there somewhere.

Second - and this one is non-negotiable - nothing in the history of raqs sharqi is defined by impermeable borders. Whenever you hear someone proclaim, “Dancers never, ever did this,” or “Egyptians always did that,” pause. Question their sources. Raise an eyebrow. Maybe raise both. And if someone confidently insists that “awalem always did things this way and this way only,” feel entirely free to disengage from that conversation altogether - there was never a strict, universally enforced rulebook that all awalem obediently followed.

Egyptian history is a landscape of fuzzy boundaries, overlaps, contradictions, and exceptions. If there was ever a single rule that was consistently applied and widely followed, it would be this one: the rule of bending the rules.

For a full list of sources used to compile this little dictionary of terms, to express your disagreement with anything I’ve said, or simply to point out the difference between a candelabrum and a candelabra, feel free to get in touch. askauntiehelen@gmail.com